- Quarter Zip Sports

- Posts

- Six Quarterbacks Before Brady: A Draft Day What-If

Six Quarterbacks Before Brady: A Draft Day What-If

Plus, Quarter Zip Investigates Whitey Bulger's Death in Prison

Every football fan knows the story: Tom Brady, pick No. 199 in the 2000 NFL Draft, walks into the New England Patriots facility as an unheralded sixth-rounder and leaves the game 23 years later as the greatest quarterback of all time. But what’s sometimes forgotten is that six other quarterbacks heard their names called before Brady ever did. Let’s take a stroll down memory lane, revisiting who they were, what they did in college, and how their NFL careers shook out.

Chad Pennington — 1st Round, Pick 18, New York Jets

If you were ranking “safe bets” in 2000, Pennington looked the part. At Marshall, he threw for over 14,000 yards, led the Thundering Herd to an undefeated season, and picked up hardware like the Sammy Baugh Trophy and MAC MVP.

In the NFL, Pennington was smart, accurate, and tough. He led the league in completion percentage twice, won Comeback Player of the Year twice, and guided both the Jets and Dolphins to playoff appearances. The downside? Injuries robbed him of longevity. Still, of all the QBs picked before Brady, Pennington had the most respectable career.

Dolphins Chad Pennington. Hell Yeah

#PhinsUp— Cameron Sparks (@Cam3ronSparks)

11:41 AM • Jun 13, 2025

Giovanni Carmazzi — 3rd Round, Pick 65, San Francisco 49ers

Carmazzi was a small-school star at Hofstra, setting program records with more than 9,000 passing yards and 71 touchdowns. He was accurate, cerebral, and seemed like a West Coast Offense fit.

Unfortunately, his NFL career never left the runway. Carmazzi never played a regular-season snap, spending time in NFL Europe and the CFL before leaving football entirely. He later admitted he never even watched Brady’s Super Bowl wins — living a quiet life on a farm in California instead.

Chris Redman — 3rd Round, Pick 75, Baltimore Ravens

Redman was a Louisville legend, winning the Johnny Unitas Golden Arm Award and setting multiple school passing records. He was known for his pocket presence and ability to spread the ball around.

In the pros, Redman spent time as a backup in Baltimore (where he earned a Super Bowl ring in 2000) and later in Atlanta. He started a handful of games for the Falcons, even flashing a bit of that college poise, but never truly became “the guy.” Career numbers: just over 3,000 passing yards and 21 touchdowns.

Tee Martin — 5th Round, Pick 163, Pittsburgh Steelers

Martin’s claim to fame? Leading Tennessee to the 1998 national championship after Peyton Manning graduated. He even set an NCAA record for 23 straight completions in a game.

The NFL didn’t pan out the same way. Martin saw limited action with the Steelers and Raiders before heading to NFL Europe and the CFL. But he found his groove in coaching — climbing the ladder through college programs like USC and Tennessee, and now serving as an NFL assistant.

Marc Bulger — 6th Round, Pick 168, New Orleans Saints

Bulger was a productive passer at West Virginia, throwing for over 8,000 yards and 59 touchdowns. Drafted by the Saints, he was quickly cut and landed in St. Louis — where he made the most of his second chance.

With the Rams, Bulger became a two-time Pro Bowler, throwing for more than 22,000 yards and 122 touchdowns. For a stretch in the early 2000s, he kept the “Greatest Show on Turf” humming after Kurt Warner’s departure. While not Hall of Fame material, he was a legitimate NFL starter for nearly a decade.

Marc Bulger with a pair of touchdowns -- the first to Isaac Bruce, the second to Torry Holt, giving STL the NFC West title. Joe Buck with the call. (2003) #STLRams

— St. Louis Rams History (@STLRamsHistory)

5:45 PM • May 20, 2024

Spergon Wynn — 6th Round, Pick 183, Cleveland Browns

Wynn played at Southwest Texas State (now Texas State) after transferring from Minnesota. He had the size and arm strength scouts liked, but not much in the way of production.

In Cleveland, Wynn was thrown into the fire on an expansion-era roster with little talent around him. He appeared in only 10 NFL games, starting three, with one career touchdown pass. He later spent a brief stint in the CFL before hanging it up.

The Draft Day Lesson

On paper, none of these six quarterbacks looked like bad picks at the time. Pennington had polish. Carmazzi had smarts. Redman had pedigree. Martin had a championship ring. Bulger had a live arm. Wynn had size.

Brady? He had a mediocre combine, a 40-yard dash time you could beat in gym class, and a Michigan career where he split snaps with Drew Henson. He didn’t fit the prototype.

But here’s the thing: the draft can measure size, speed, and stats. It can’t measure drive, resilience, or the obsessive will to win. And that’s where Brady crushed everyone — not just in his class, but in NFL history.

If you lined up these seven quarterbacks in April 2000 and asked every GM to pick the guy who’d win seven Super Bowls, only one coach would have raised his hand — and that was Bill Belichick, 18 months later, when he benched Drew Bledsoe and handed the keys to No. 12.

The rest, as they say, is football’s greatest “what if” story.

The first phone call with our 199th pick in the 2000 NFL Draft…

…the rest is history, @TomBrady.

— New England Patriots (@Patriots)

3:45 PM • Aug 31, 2023

New York Jets (Chad Pennington, 1st Round)

On paper, this could have been interesting. The Jets had Vinny Testaverde, solid weapons, and a good defense. But they were also in a constant state of coaching turnover, and the New York media circus isn’t exactly a warm incubator for a sixth-round project. Without Belichick — who left the Jets for New England the day after being named head coach — Brady might never have gotten the patience he needed.

San Francisco 49ers (Giovanni Carmazzi, 3rd Round)

The hometown dream. Brady grew up a Joe Montana disciple, so there’s a romance to this fit. But the Steve Mariucci-era Niners were looking for a mobile, West Coast guy — and Brady was neither. Plus, Jeff Garcia had just arrived and played well. Nostalgia aside, probably not a great launchpad.

Baltimore Ravens (Chris Redman, 3rd Round)

Forget it. The 2000 Ravens were the definition of defense-first. They won the Super Bowl with Trent Dilfer throwing for 153 yards a game. Developing a young quarterback wasn’t in their DNA at the time.

Pittsburgh Steelers (Tee Martin, 5th Round)

Now we’re talking. The Steelers had stability under Bill Cowher, a strong run game, and a defense that could buy time for a developing QB. Kordell Stewart was the starter, but Brady might have quietly climbed the depth chart here and thrived in Pittsburgh’s blue-collar, methodical system.

New Orleans Saints (Marc Bulger, 6th Round)

This one’s a mess. The Saints of 2000 were rebuilding under Jim Haslett and didn’t have the infrastructure for a long-term QB project. Bulger never stuck there either, finding success later in St. Louis — so it’s hard to see Brady’s legend starting in the Superdome.

Cleveland Browns (Spergon Wynn, 6th Round)

Hard no. Expansion-era Browns football was a graveyard for quarterbacks. Bad line, bad weapons, bad coaching. Brady might have been broken before he ever got going.

If there was one team that could have been a “Patriots alternate universe,” it’s probably the Steelers — stability, structure, and a coach who valued toughness. But let’s be real: the Patriots’ unique mix of patience, coaching, and timing was lightning in a bottle. Anywhere else, we might just remember Tom Brady as “that backup from Michigan who had a decent run.”

At least if the Steelers had drafted Brady, he would have tortured them less.

When Tom Brady entered the 2000 NFL Draft, few teams saw him as a future franchise quarterback. Scouts were hesitant for several reasons, many of which were rooted in how Brady presented physically and athletically. His NFL Combine performance did him no favors — he ran a sluggish 5.28-second 40-yard dash, looked lanky and underdeveloped at 6'4", 211 pounds, and lacked the arm strength that typically excites decision-makers. His combine photo, still circulated today, became a symbol of everything scouts were unsure about.

Beyond the measurables, Brady’s college resume was respectable but unspectacular. He spent most of his Michigan career in a quarterback competition, only starting full-time his senior year. Even then, he was frequently rotated with Drew Henson — a younger, more physically gifted quarterback the Michigan coaching staff seemed eager to promote. While Brady led multiple late-game comebacks and showed grit and poise, evaluators questioned why he couldn’t solidify his position sooner.

Tom Brady had ice water in his veins during his final game as a Michigan Wolverine. Just a sample size of what we would see during his NFL career

Tom Brady passing: 34/46 369 yards 4 TD 0 INT

David Terrell receiving: 10 rec 150 yards 3 TD

Michigan win over Alabama in OT

— Jake B 〽️ (@MichFootballBEL)

7:10 PM • Feb 15, 2025

There was also a systemic bias in the scouting world at the time: teams often prioritized tools over intangibles. Brady didn’t "wow" anyone in shorts or drills. He wasn’t a dual-threat QB, he didn’t have a cannon for an arm, and his throwing mechanics were viewed as just average. In short, he didn’t fit the prototype.

What scouts overlooked were the things that can’t be measured — leadership, competitiveness, football IQ, and relentless work ethic. It’s a lesson that continues to haunt teams who passed on him: you can’t always evaluate greatness with a stopwatch.

Have you subscribed to the email newsletter?

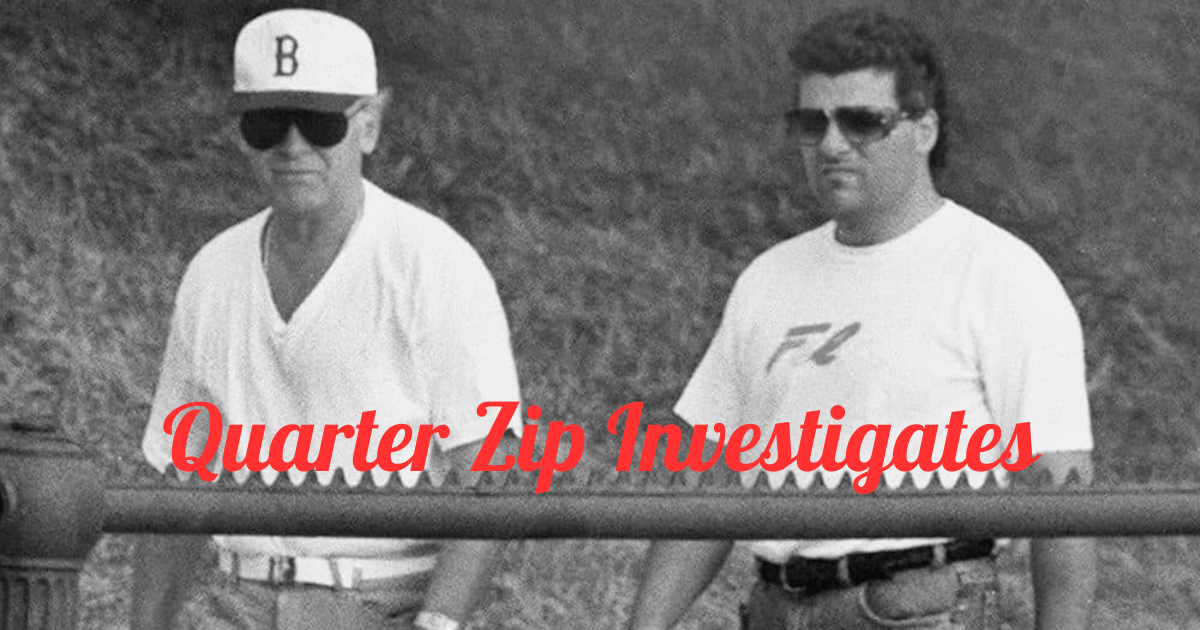

This undated surveillance photo shows James "Whitey" Bulger, left, walking with his former right-hand man, Kevin Weeks. (U.S. Attorney's Office)

Whitey Bulger’s Final Chapter: Murder in a West Virginia Prison

James “Whitey” Bulger lived a life that seemed ripped from the pages of a crime novel — and his death was no less cinematic. The 89-year-old Boston mob boss, fugitive, and FBI informant was beaten to death in his cell at a West Virginia federal prison on October 30, 2018, less than 12 hours after his arrival. Even for a man who had dodged justice for decades, the ending felt swift, brutal, and almost inevitable.

From King of Southie to Prison Transfer

Bulger’s violent end came after a long fall from power. Once the leader of the Winter Hill Gang, he ruled South Boston for decades, mixing calculated charm with ruthless intimidation. For years, the FBI — particularly agent John Connolly — shielded him in exchange for intel on the Italian mob. But when the heat finally closed in, Bulger vanished in 1994, sparking one of the longest manhunts in U.S. history. He was finally arrested in 2011 in Santa Monica, living quietly with his girlfriend in a rent-controlled apartment.

Former mob boss James "Whitey" Bulger and his girlfriend were apprehended by Deputy U.S. Marshals and FBI agents. Extradited to Boston to face 19 murder charges, Bulger’s assets were auctioned by the AFD in 2016, benefiting the families of his victims.

#USMarshals

— U.S. Marshals Service (@USMarshalsHQ)

2:01 PM • Dec 18, 2024

In 2013, Bulger was convicted of 31 counts, including racketeering, extortion, money laundering, and direct involvement in 11 murders. He was sentenced to two consecutive life terms plus five years — a poetic punctuation mark for a man who had lived outside the law for so long.

Initially, Bulger was held at high-security facilities, including the infamous USP Tucson, which houses many inmates who require protection. But in late October 2018, the Bureau of Prisons abruptly transferred him to USP Hazelton in West Virginia — a maximum-security prison with a reputation for violence and understaffing.

Less Than a Day to Live

Bulger’s arrival at Hazelton was his death sentence. Within hours, fellow inmates reportedly learned of his transfer. News travels fast in prison, especially when the new arrival is a high-profile “rat” with enemies on every tier. By the morning of October 30, Bulger was found unresponsive in his cell, his body beaten so badly that he was reportedly unrecognizable.

BREAKING NEWS: Notorious Boston mobster Whitey Bulger was killed in a West Virginia prison Tuesday, sources told WBZ-TV I-Team chief correspondent Cheryl Fiandaca boston.cbslocal.com/2018/10/30/whi…

— WBZ | CBS News Boston (@wbz)

4:51 PM • Oct 30, 2018

The attack was not subtle. Sources later indicated he was struck repeatedly in the head, possibly with a padlock in a sock — a common makeshift prison weapon. His wheelchair, which he used in later years due to heart issues, offered no protection. Whoever killed him had both the time and the confidence to make the assault personal and thorough.

Prime Suspects and Prison Politics

While no one has been officially convicted for the murder, suspicion quickly fell on a small group of inmates with ties to organized crime. One name emerged in media reports almost immediately: Fotios “Freddy” Geas, a former Mafia hitman from Massachusetts serving a life sentence for the murders of Springfield mob boss Adolfo “Big Al” Bruno and associate Gary Westerman.

Geas, who reportedly despised informants, would have had a clear motive. In the criminal underworld — and especially inside prison — being labeled a rat is the ultimate stain. Bulger’s long-documented cooperation with the FBI made him a trophy target.

Federal prisoner Fotios “Freddy” Geas was sentenced on Friday in the 2018 fatal prison bludgeoning of notorious Boston gangster James “Whitey” Bulger.

Read more: boston25.com/4eeJy8I

— Boston 25 News (@boston25)

4:45 PM • Sep 6, 2024

Other factors made Hazelton a dangerous environment for Bulger. The prison had been criticized for staffing shortages and rising violence, conditions that give powerful inmates more leeway. The transfer decision itself remains controversial; why move an elderly, high-profile inmate with known enemies into a volatile setting with minimal protective measures?

Retribution or Convenience?

Bulger’s murder has fueled two competing narratives.

The first is straightforward retribution: Inmates with mob connections saw a chance to eliminate a notorious informant and took it. It fits the underworld code — and Bulger had no shortage of enemies, both inside and outside the Italian-American Mafia.

The second theory is darker: that his death was, in part, facilitated by the system that once protected him. Some former law enforcement officials have suggested the Bureau of Prisons knew the risks of transferring Bulger to Hazelton and either underestimated the danger or turned a blind eye. Given Bulger’s history — and the embarrassment he caused the FBI — conspiracy theories about a “green light” from higher up have persisted.

The Irony of a Violent End

For decades, Bulger had managed to skirt the consequences of his own brutality, protected by both fear and federal connections. His criminal career was marked by calculated moves to stay one step ahead — whether through corrupt FBI ties, sudden disappearances, or sheer intimidation.

That his life ended in a prison cell, at the hands of other criminals, carries a sense of poetic justice for many of his victims’ families. It was an ending that stripped away the layers of mythology surrounding Bulger and reminded the public that, for all his cunning, he was not untouchable.

Legacy in the Shadows

Bulger’s death closed the book on one of the most notorious chapters in Boston’s criminal history, but his legacy remains complicated. To some in South Boston, he was a Robin Hood figure, a man who “kept drugs out” (though evidence shows he profited heavily from them). To his victims and their families, he was a murderer, extortionist, and master manipulator who inflicted lasting trauma.

His murder in prison ensured that he would never face further questioning, never reveal deeper truths about his relationship with the FBI, and never provide closure to those who wondered how far his influence truly went. In that sense, the final mystery of Whitey Bulger is not just who killed him — but how much more of the story died with him.

Quarter Zip Investigates

Reply